Montaigne and The Art of Living

Lead Professors: Giulia Oskian and Steven B. Smith

EverScholar in New York

April 28 – May 1, 2022

Course has completed.

Listen to our faculty discuss the Montaigne course in this video.

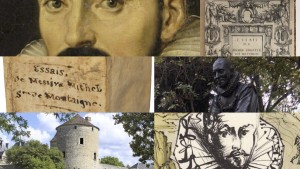

The modern world began on February 28, 1571. On that day a French nobleman by the name of Michel de Montaigne retired from his public duties as a member of the Bordeaux parlement, moved roughly one thousand volumes into the third floor of a circular tower attached to the family chateau, and began work on the book simply titled Essays that would occupy the rest of his life.

“I am myself the matter of my book; you would be unreasonable to spend your leisure on so frivolous and vain a subject,” Montaigne warned the reader in the introduction to this work. The Essays was unlike any book that had ever been written before. The title is from the French verb essayer meaning to struggle, to attempt, to try. The book was never intended to be a finished product but rather a series of efforts to grasp the changing nature of that most elusive object, the self. By putting himself at the center of his work –the je or I with its changing moods, perceptions, and desires — Montaigne not only launched a new literary genre but created a new world.

Montaigne’s work is not an autobiography in the strict sense but along the way he manages to tell us a great deal about himself. He was born in 1533 in a chateau about thirty miles from Bordeaux. The family name was originally Eyquem and their fortune was originally acquired through a fish and wine importing business. His father, Pierre, was the first to use the name Montaigne; his mother Antoinette de Louppes (nLopez) was of Jewish descent, descended from Spanish Marranos.

Montaigne married – rather unhappily it seems – Francoise de la Chassaigne who bore six children, only one of whom a daughter, Leonor would survive to adulthood. They are scarcely mentioned in his book. With the death of his father in 1568, the thirty-four year old Montaigne found himself head of the household and free to pursue the way of life for which he had been preparing.

Montaigne worked on his Essays for over twenty years, continually adding and revising, to give the reader the fullest sense of its author and his way of life. There are 107 essays in total, the longest and most famous “The Apology of Raymond Sebond” being more than 150 pages, the shortest being no more than a page or two. The book covers a remarkable set of topics, moral, religious, psychological, and political. Despite his claims to deal with only private themes, the Essays teem with allusions to the great issues of the day – the wars of religion, and the discovery and conquest of the New World. Montaigne was instrumental in the revival of skepticism which he used not in order dispel religion but to undermine the pretentions of reason.

The defining political issue of Montaigne’s life was the struggle between Catholics and Protestants that shook all of Europe in the wake of the Reformation. The Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572 initiated a series of pogroms throughout France that continued for several months leading to a period of protracted violence and civil war. These events occasioned some of his sharpest reflections on the dangers of moral certainty and the importance of moderation and pragmatism. In 1581, Montaigne was called out of retirement to serve as mayor of Bordeaux where he attempted to mediate between the city’s Catholic and Protestant populations. Montaigne’s advocacy for policies of clemency, mercy, and, above all, the avoidance of cruelty grew out of this experience and runs like a bright line throughout the Essays.

Even during his final years, Montainge’s life was scarcely peaceful. He was forced to abandon his estate due to the onset of a plague. He remained an advisor to Henry of Navarre who visited his chateau in 1587, but he did not live to see Navarre become King Henry IV and convert to Catholicism, nor did he see him broker a treaty – the Edict of Nantes in 1598 – that would bring a truce to the warring parties. It would stand for almost a century until it was revoked by Louis XIV in 1685.

Montaigne was not a political philosopher in the strict sense. He left no treatise on government, but he was an early advocate of toleration, a defender of a sphere of private liberty, and an outspoken critic of policies of cruelty and persecution that make him a forerunner of political liberalism. At the same time, Montaigne remained a loyal subject of the king, praised the power of custom, and continually warned against the danger of political reformers. What were the politics of Montaigne’s Essays will be an on-going theme of our course.

Montaigne’s Essays were immediately popular. A first edition appeared in 1580 and immediately sold out. Much expanded editions appeared in 1582, 1587, and 1588. The first English translation by John Florio appeared in 1603, less than a decade after Montaigne’s death. A second translation appeared later in the century. The Donald Frame translation that we will be using was published in 1958 and an even more recent translation by M. A. Screech appeared in the early 2000’s. Montaigne’s Essays spawned imitators. Francis Bacon’s book titled Essays appeared in 1597. Ralph Waldo Emerson – a great admirer of Montaigne – who gave the essay its American form devoted a chapter titled “Montaigne or the Skeptic” in his book Representative Men.

This course will allow us to study this amazing man and the book that launched modernity.

How will we study it? Through close reading of the essays themselves. Through reading short writings by and about Montaigne’s contemporaries; his influences; his inheritors. The difficulty in classifying Montaigne is a blessing, for it allows us to explore him as semi-political philosopher, historian, literary figure – perhaps even a therapist of sorts. Finally, we will explore what it might mean to approach Montaigne’s project if one wished to create it, today.

Our faculty are a dream team of Montaigne explorers. Our leaders, Profs. Smith and Oskian, team-taught a semester-long version of this course at Yale College. You are invited to watch a conversation between them in the video elsewhere on this page, to see the obvious fruits of this labor. As guest faculty, we have professors from three institutions who are renowned not only for their Montaigne knowledge but for their love of teaching and their incredible bodies of intellectual achievement.

One is tempted to answer the question implicit in this course’s title – How does one live an artful life – with a simple answer: one takes this course.

Our Lead Faculty:

Our Guest Faculty:

The course begins with a reception and dinner on Thursday…. and ends after dinner Sunday evening. The program cost is $1,995 per person. Deposit is $500 per person. Balance is due on April 1. Generous refund and full COVID-19 refund policies are detailed on registration page (click on “Register Now” button above for this information along with accommodation details) – you can register without worries. Looking forward to seeing you there!